American wine connoisseurs tend to interact with their beloved beverage in the aisles of a retail store, in a restaurant, or at home at their own table. We understand that wine is the product of vineyards, but spend very little time thinking about the rhythms of nature and the actual biological processes of the vine. A basic understanding of the botanical cycle of grape growing can enhance the understanding of and appreciation for wine.

The French term for winemaker is “vigneron,” (“vin-yuh-RAHN”) which translates to “a person who grows grapes for winemaking.” This reflects a philosophical attitude that values the vineyard over the cellar as the principal place where wine originates. One might say that the French see wine as a product that is grown, rather than made. The distinction is important for American consumers who are more likely to see wine through an industrial lens as a manufactured product. Wine is, of course, the product of both the vineyard and the cellar, but this article will focus on the former: the vine, vineyards, and grapes that provide wine lovers with so much pleasure.

Challenges for Winegrowers

It’s hard to overstate the vulnerability of grapevines during the various stages of the growing season. Spring frost can kill young shoots, heavy rain can lead to rot, bugs can eat tender leaves, birds can eat the grapes, and hail can devastate the entire vineyard. Factors like these are the cause of vintage variability. Understanding the grape’s treacherous journey from the vine to the bottle can also lead to a particular appreciation for a good wine.

The Seasons

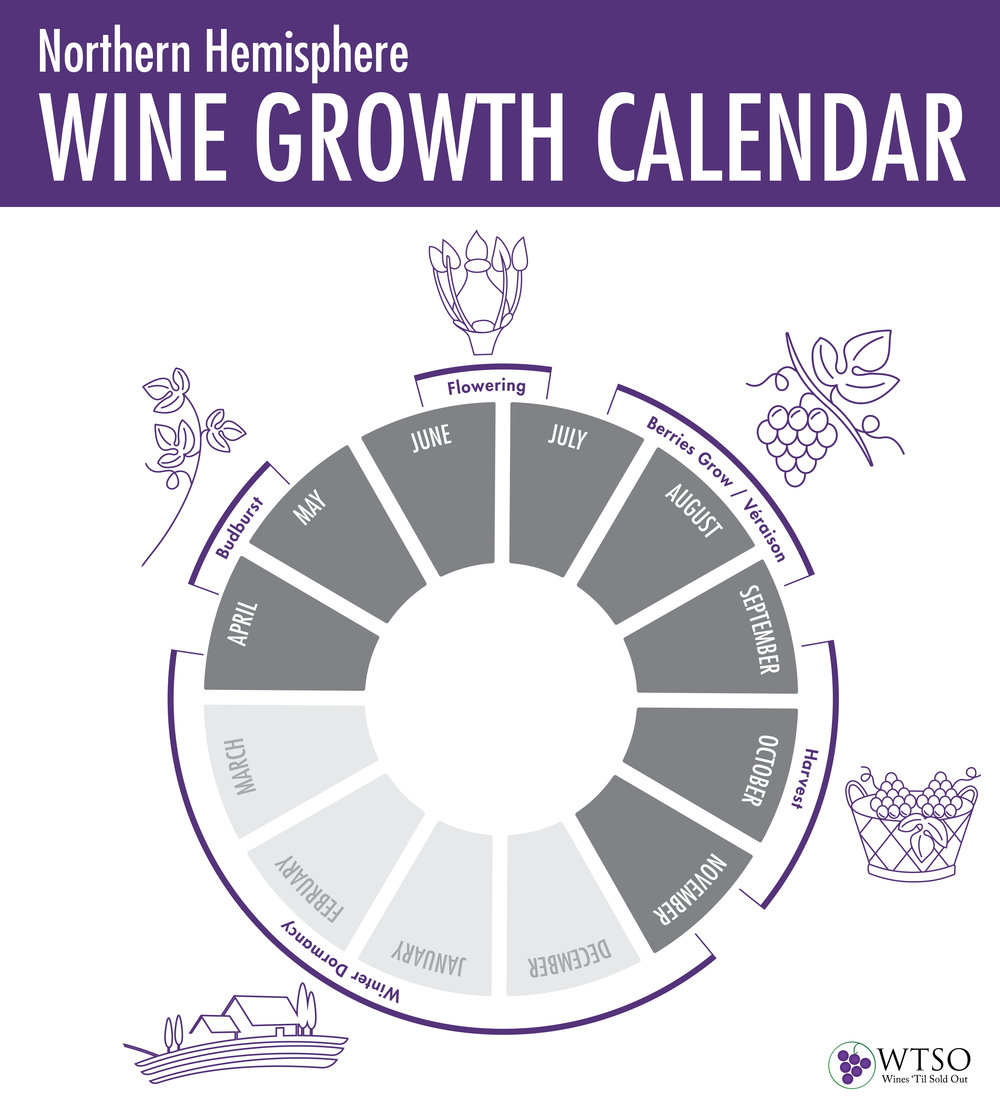

The first phase in the new growing season occurs between April and May. New shoots begin to grow from buds dormant over the winter and formed the previous season. These shoots grow throughout the summer and form the structures for later flowering and fruiting.

Flowering begins either in June or July. Vitis Vinifera, the European vine responsible for most fine wine production, is hermaphroditic, and a single vine can pollinate itself. Fruit set occurs shortly thereafter, and the tiny grapes begin to develop. Individual grapes are referred to as berries.

July through September sees the growth of the berries and a brief, but crucial phase called “véraison” – when they change color. It’s important that the weather cooperates during this phase, to produce good quality fruit. There should be plenty of sunlight, without too many extremes of temperature.

The most important and commonly discussed phase of the season occurs in the late summer and fall, when the grapes ripen and are harvested. Earlier in the summer, the berries will have strong, bitter, acidic flavors that transform into the sweet, soft, complex taste of ripe grapes. Winegrowers spend many sleepless nights in the weeks leading up to the harvest, hoping that their crops are spared from bad weather and pests. Traditionally, winegrowers would determine the harvest time by tasting the grapes in the vineyard. When they decided that the flavor was right, they would begin the harvest. Today, many modern techniques have been developed to test the chemical content of the grapes, including the acid and sugar levels, to determine the perfect time for harvest. Once the decision has been made, the grapes can be harvested by hand or by machine. Harvest usually takes place between September and November.

After the harvest, the vines lose their leaves, entering a state called “winter dormancy,” wherein metabolic activity is minimized. This period of dormancy is dependent on temperature, as Vinifera wines cannot come from climates that are too warm. Cold winters are necessary for healthy Vinifera vines – even in climates suited to grape growing, unexpected warm periods in the winter may cause premature bud break and damage to the vines.